Wine, Trangression and Excess

Ackland Museum Exhibit, 2015

Wine, Transgression and Excess

By the students in Professor Inger Brodey’s “The Feast in Philosophy, Film, and Fiction” course in Spring, 2015 (ASIA 255H /CMPL 255H)

Cultures far and wide have discovered the practicalities and pleasures of fermented fruit or grain, particularly in producing alcoholic beverages. Echoes of these beverages can be seen in the vessels on display in this gallery: the small sake cup for Japanese rice wine; the ancient Greek lacquer-ware kylix for sharing wine in a symposium setting; the German glass Pilsner Stein for drinking beer; the Kiddush cup for the communal consumption of sweet grape wine during the Jewish Shabbat; and from China, both the porcelain tankard made for European beer consumption as well as the much older porcelain wine vessel used domestically for pouring rice wine into smaller vessels.

Leon Kass describes the attraction of these kindred beverages: “Wine gladdens the heart, loosens the tongue, and enlivens the soul. Under its influence, we forget our troubles, lose our inhibitions, speak our minds: In vino veritas. A psychic midwife, wine delivers us of hidden insights and new affections” (The Hungry Soul, 125). In our readings, particularly Plato’s Symposium and T.S. Eliot’s response to Plato in his play The Cocktail Party, we can see that alcohol is associated with insight and can function as a psychic medicine at times.

And yet, Plato’s Symposium also witnesses the drunken and unmeasured behavior of at least one of its guests. To quote again from Leon Kass’ The Hungry Soul: “wine, like other human foods … partakes of the moral ambiguity of the human. […] It can enhance and it can destroy [our] humanity” (127). No object could testify better to the excesses associated with the culture of alcohol consumption than the porcelain “vomit pot” in our exhibition.

Wine also suggests the insatiable aspects of human curiosity and hunger. Historically, this insatiability reveals itself in the (establishment of and) transgression of cultural taboos. Both lithographs on display here depicted a violation of food taboos, both in quantity and choice of meat: in one a man violates the taboo against eating horse meat and in the other, the Lord Mayor violates a variety of religious and other taboos in his gluttonous dream.

Tea and its kindred caffeine-bearing beverages (including coffee and drinking chocolate), also manifest themselves differently across material cultures, while simultaneously pointing to shared human needs that unite the human experience. Both the German glass cup and saucer and the albumen print of the simulated Japanese tea gathering attest to the lasting and sophisticated associations with tea, a drink whose attraction originated in its power to overcome (or at least delay) the need to sleep.

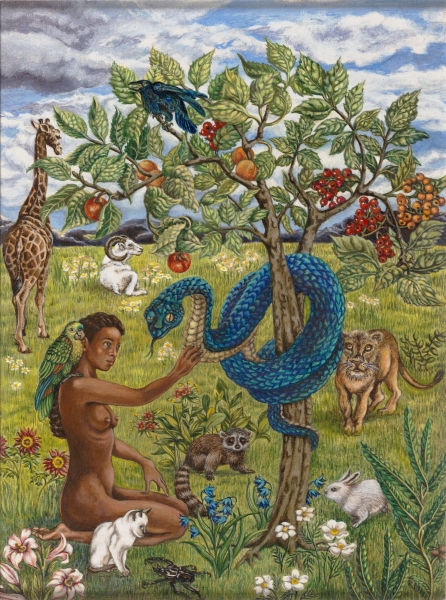

Finally, two of the pieces on display relate to specific religious connections between food and sin, as understood in the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition. Rose Piper’s depiction of Eve and the serpent from the Book of Genesis depicts fallen human nature through an act of temptation and eating. La Ultima Cena poster depicts not only the Last Supper where Jesus proleptically commemorates his redemption of sin through an act of eating, drinking, and remembrance and by emphasizing the connection between blood and wine. We have come full circle: wine like culture can either enlighten us or reveal violence or concupiscence suppressed beneath the surface of our polished surroundings.

Many thanks to Sarah Elizabeth Morris, Caroline Culbert, and especially Carolyn Allmendinger for helping our class assemble this exhibit and guide book.

–Inger Sigrun Brodey